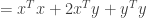

Exercise 3.2.1. a) Consider the vectors  and

and  where

where  and

and  are arbitrary positive real numbers. Use the Schwarz inequality involving

are arbitrary positive real numbers. Use the Schwarz inequality involving  and

and  to derive a relationship between the arithmetic mean

to derive a relationship between the arithmetic mean  and the geometric mean

and the geometric mean  .

.

b) Consider a vector from the origin to point  , a second vector of length

, a second vector of length  from

from  to the point

to the point  and the third vector from the origin to

and the third vector from the origin to  . Using the triangle inequality

. Using the triangle inequality

derive the Schwarz inequality. (Hint: Square both sides of the inequality and expand the expression  .)

.)

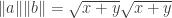

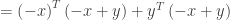

Answer: a) From the Schwarz inequality we have

From the definitions of  and

and  , on the left side of the inequality we have

, on the left side of the inequality we have

assuming we always choose the positive square root.

From the definitions of  and

and  we also have

we also have

and

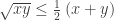

so that the right side of the inequality is

again assuming we choose the positive square root. (We know  is positive since both

is positive since both  and

and  are.)

are.)

The Schwartz inequality

then becomes

or (dividing both sides by 2)

We thus see that for any positive real numbers  and

and  the geometric mean

the geometric mean  is less than the arithmetic mean

is less than the arithmetic mean  .

.

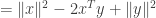

b) From the triangle inequality we have

for the vectors  and

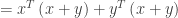

and  . Squaring the term on the left side of the inequality and using the commutative and distributive properties of the inner product we obtain

. Squaring the term on the left side of the inequality and using the commutative and distributive properties of the inner product we obtain

Squaring the term on the right side of the inequality we have

The inequality

is thus equivalent to the inequality

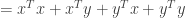

Subtracting  and

and  from both sides of the inequality gives us

from both sides of the inequality gives us

and dividing both sides of the inequality by 2 produces

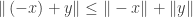

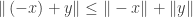

Note that this is almost but not quite the Schwarz inequality: Since the Schwarz inequality involves the absolute value  we must also prove that

we must also prove that

(After all, the inner product  might be negative, in which case the inequality

might be negative, in which case the inequality  would be trivially true, given that the term on the right side of the inequality is guaranteed to be positive.)

would be trivially true, given that the term on the right side of the inequality is guaranteed to be positive.)

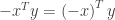

We have  . Since the triangle inequality holds for any two vectors we can restate it in terms of

. Since the triangle inequality holds for any two vectors we can restate it in terms of  and

and  as follows:

as follows:

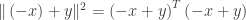

Since  squaring the term on the right side of the inequality produces

squaring the term on the right side of the inequality produces

as it did previously. However squaring the term on the left side of the inequality produces

The original triangle inequality

is thus equivalent to

or

Since we have both  and

and  we therefore have

we therefore have

which is the Schwarz inequality.

So the triangle inequality implies the Schwarz inequality.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

,

,

, and

, and the center (carbon atom) at

. What is the cosine of the angle between the rays going from the center to each of the vertices?

be the ray from

to

and

be the ray from

to

. We have

between

and

as

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.