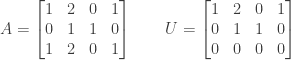

Exercise 2.4.3. For each of the two matrices below give the dimension and find a basis for each of their four subspaces:

Answer: We first consider the column spaces  and

and  . The matrix

. The matrix  has two pivots and therefore rank

has two pivots and therefore rank  ; this is the dimension of the column space of

; this is the dimension of the column space of  . Since the pivots are in the first and second columns those columns are a basis for

. Since the pivots are in the first and second columns those columns are a basis for  :

:

Note that the third column of  is equal to -2 times the first column plus the second column, and the fourth column is equal to the first column.

is equal to -2 times the first column plus the second column, and the fourth column is equal to the first column.

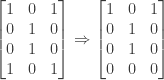

Doing Gaussian elimination on the matrix  (i.e., by subtracting the first row from the third) produces

(i.e., by subtracting the first row from the third) produces  , so the rank of

, so the rank of  and the dimension of the column space of

and the dimension of the column space of  are also 2. Also, since the first and second columns of

are also 2. Also, since the first and second columns of  (the pivot columns) are a basis for

(the pivot columns) are a basis for  the first and second columns of

the first and second columns of  are a basis for

are a basis for  :

:

Note that as with  the third column of

the third column of  is equal to -2 times the first column plus the second column, and the fourth column is equal to the first column.

is equal to -2 times the first column plus the second column, and the fourth column is equal to the first column.

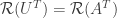

Turning to the row spaces, since the rows of  are linear combinations of the rows of

are linear combinations of the rows of  and vice versa, the row spaces

and vice versa, the row spaces  and

and  are the same. Per the discussion on page 91 the nonzero rows of

are the same. Per the discussion on page 91 the nonzero rows of  , the vectors

, the vectors  and

and  , form a basis for

, form a basis for  . Since

. Since  these vectors also form a basis for

these vectors also form a basis for  . The dimension of each row space is 2.

. The dimension of each row space is 2.

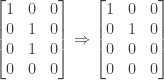

We now turn to the nullspaces  and

and  consisting of the solutions to the equations

consisting of the solutions to the equations  and

and  respectively. As noted above, if we do Gaussian elimination on

respectively. As noted above, if we do Gaussian elimination on  (i.e., by subtracting the first row from the third row) then we obtain the matrix

(i.e., by subtracting the first row from the third row) then we obtain the matrix  so that any solution to

so that any solution to  is a solution to

is a solution to  and vice versa. We therefore have

and vice versa. We therefore have  and just need to calculate one of the two.

and just need to calculate one of the two.

In particular for  we must find

we must find  such that

such that

Since the pivots of  are in the first and second columns we have

are in the first and second columns we have  and

and  as basic variables and

as basic variables and  and

and  as free variables.

as free variables.

From the second row of the system above we have  or

or  . From the first row we then have

. From the first row we then have  or

or  . Setting each of the free variables

. Setting each of the free variables  and

and  to 1 in turn (and the other free variable to zero) we have the following set of vectors as solutions to the homogeneous equation

to 1 in turn (and the other free variable to zero) we have the following set of vectors as solutions to the homogeneous equation  and a basis for the null space of

and a basis for the null space of  :

:

Since  the above vectors also form a basis for the nullspace of

the above vectors also form a basis for the nullspace of  . The dimension of the two nullspaces

. The dimension of the two nullspaces  and

and  is 2 (the number of columns of each matrix minus the rank, or

is 2 (the number of columns of each matrix minus the rank, or  ).

).

Finally we turn to finding a basis for each of the left nullspaces  and

and  . As discussed on page 95 there are two possible approaches to doing this. One way to find the left nullspace of

. As discussed on page 95 there are two possible approaches to doing this. One way to find the left nullspace of  is to look at the operations on the rows of

is to look at the operations on the rows of  needed to produce zero rows in the resulting echelon matrix

needed to produce zero rows in the resulting echelon matrix  in the process of Gaussian elimination; the coefficients used to carry out those operations make up the basis vectors of the left nullspace

in the process of Gaussian elimination; the coefficients used to carry out those operations make up the basis vectors of the left nullspace  .

.

In particular, the one and only zero row in  is produced by subtracting the first row of

is produced by subtracting the first row of  from the third row of

from the third row of  , with no contribution from the second row; the coefficients for this operation are -1 (for the first row), 0 (for the second row), and 1 (for the third). The vector

, with no contribution from the second row; the coefficients for this operation are -1 (for the first row), 0 (for the second row), and 1 (for the third). The vector

is therefore a basis for the left nullspace  (which has dimension 1). We can test this by multiplying

(which has dimension 1). We can test this by multiplying  on the left by the transpose of this vector:

on the left by the transpose of this vector:

The left nullspace of  can be found in a similar manner: Since

can be found in a similar manner: Since  is already in echelon form with a third row of zeroes, the step of Gaussian elimination to produce that row would be equivalent to multiplying the first row by zero and the second row by zero and then adding them to the third (zero) row; the coefficients for this operation are 0 (for the first row), 0 (for the second row), and 1 (for the third row). The vector

is already in echelon form with a third row of zeroes, the step of Gaussian elimination to produce that row would be equivalent to multiplying the first row by zero and the second row by zero and then adding them to the third (zero) row; the coefficients for this operation are 0 (for the first row), 0 (for the second row), and 1 (for the third row). The vector

is therefore a basis for the left nullspace  (which also has dimension 1). As with

(which also has dimension 1). As with  we can test this by multiplying

we can test this by multiplying  on the left by the transpose of this vector:

on the left by the transpose of this vector:

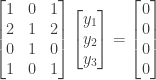

An alternate approach to find the left nullspace of  is to explicitly solve

is to explicitly solve  or

or

Gaussian elimination on  proceeds as follows: First, subtract two times the first row from the second:

proceeds as follows: First, subtract two times the first row from the second:

and then subtract the first row from the fourth row:

Finally, subtract the second row from the third row:

We thus have  and

and  as basic variables (since the pivots are in the first and second columns) and

as basic variables (since the pivots are in the first and second columns) and  as a free variable. From the first row of the final matrix we have

as a free variable. From the first row of the final matrix we have  or

or  in the homogeneous case, and from the second row of the final matrix we have

in the homogeneous case, and from the second row of the final matrix we have  or

or  . Setting the free variable

. Setting the free variable  then gives us the vector

then gives us the vector

as a basis for the left nullspace of  . The left nullspace of

. The left nullspace of  has dimension 1 (the number of rows of

has dimension 1 (the number of rows of  minus its rank, or

minus its rank, or  ).

).

Similarly we can also find the left nullspace of  by solving the homogeneous system

by solving the homogeneous system  or

or

Gaussian elimination on  proceeds as follows: First, subtract two times the first row from the second:

proceeds as follows: First, subtract two times the first row from the second:

and then subtract the first row from the fourth row:

Finally, subtract the second row from the third row:

We thus have  and

and  as basic variables (since the pivots are in the first and second columns) and

as basic variables (since the pivots are in the first and second columns) and  as a free variable. From the first row of the final matrix we have

as a free variable. From the first row of the final matrix we have  or

or  in the homogeneous case, and from the second row of the final matrix we have

in the homogeneous case, and from the second row of the final matrix we have  or

or  . Setting the free variable

. Setting the free variable  then gives us the vector

then gives us the vector

as a basis for the left nullspace of  . As with

. As with  the left nullspace of

the left nullspace of  has dimension 1 (the number of rows of

has dimension 1 (the number of rows of  minus its rank, or

minus its rank, or  ).

).

As with exercise 2.4.2, note that the row space of  is equal to the row space of

is equal to the row space of  because the rows of

because the rows of  are linear combinations of the rows of

are linear combinations of the rows of  and vice versa. Similarly the nullspace of

and vice versa. Similarly the nullspace of  is equal to the nullspace of

is equal to the nullspace of  for the same reason.

for the same reason.

UPDATE: Corrected two typos involving the equations for the left nullspace; thanks to Lucas for finding the errors.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

the system

has at least one nonzero solution. Show that there exists at least one vector

for which the system

has no solution. Show an example of such a matrix

and vector

.

is an

by

matrix. If there exists a nonzero

for which

then the columns of

are linearly dependent. (If they were linearly independent then

would imply that

for all

.) We therefore have the rank

.

and the dimension of the row space

is equal to

the dimension of

is less than

. In other words, the rows of

do not span all of

.

in

that is not in

and cannot be expressed as a linear combination of the rows of

. Therefore for the vector

there is no solution to the system

. (If there were such a solution then its coefficients

would define a linear combination of the rows of

equal to

.)

is equivalent to

with

as a basic variable and

as a free variable.

or

. If we set the free variable

to 1 we then have

and

as a (nonzero) solution to

.

is a basis for the row space

, which consists of all vectors of the form

. Geometically this is a line through the origin and the point

.

, and consider the vector

and the system

while the second equation produces

, a contradiction. There is thus no solution to

for the example values of

and

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.