Review exercise 2.26. State whether the following statements are true or false:

a) For every subspace  of

of  there exists a matrix

there exists a matrix  for which the nullspace of

for which the nullspace of  is

is  .

.

b) For any matrix  , if both

, if both  and its transpose

and its transpose  have the same nullspace then

have the same nullspace then  is a square matrix.

is a square matrix.

c) The transformation from  to

to  that transforms

that transforms  into

into  (for some scalars

(for some scalars  and

and  ) is a linear transformation.

) is a linear transformation.

Answer: a) For the statement to be true, for any subspace  of

of  we must be able to find a matrix

we must be able to find a matrix  such that

such that  . (In other words, for any vector

. (In other words, for any vector  in

in  we have

we have  and for any

and for any  such that

such that  the vector

the vector  is an element of

is an element of  .)

.)

What would such a matrix  look like? First, since

look like? First, since  is a subspace of

is a subspace of  any vector

any vector  in

in  has four entries:

has four entries:  . If we have

. If we have  then the matrix

then the matrix  must have four columns; otherwise

must have four columns; otherwise  would not be able to multiply

would not be able to multiply  from the left side.

from the left side.

Second, note that the nullspace of  and the column space of

and the column space of  are related: If the column space has dimension

are related: If the column space has dimension  then the nullspace of

then the nullspace of  has dimension

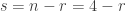

has dimension  where

where  is the number of columns of

is the number of columns of  . Since

. Since  has four columns (from the previous paragraph) the dimension of

has four columns (from the previous paragraph) the dimension of  is

is  .

.

Put another way, if  is the dimension of

is the dimension of  and

and  is the nullspace of

is the nullspace of  then we must have

then we must have  or

or  . So if the dimension of

. So if the dimension of  is

is  then we have

then we have  , if the dimension of

, if the dimension of  is

is  then we have

then we have  , and so on.

, and so on.

Finally, if the matrix  has rank

has rank  then

then  has both

has both  linearly independent columns and

linearly independent columns and  linearly independent rows. As noted above, the number of columns of

linearly independent rows. As noted above, the number of columns of  (linearly independent or otherwise) is fixed by the requirement that the nullspace of

(linearly independent or otherwise) is fixed by the requirement that the nullspace of  should be a subspace of

should be a subspace of  . So

. So  must always have four columns, and must have at least

must always have four columns, and must have at least  rows.

rows.

We now have five possible cases to consider, and can approach them as follows:

has dimension 0 or 4. In both these cases there is only one possible subspace

has dimension 0 or 4. In both these cases there is only one possible subspace  and we can easily find a matrix

and we can easily find a matrix  meeting the specified criteria.

meeting the specified criteria. has dimension 1, 2, or 3. In each of these cases there are many possible subspaces

has dimension 1, 2, or 3. In each of these cases there are many possible subspaces  (an infinite number, in fact). For a given

(an infinite number, in fact). For a given  we do the following:

we do the following:

- Start with a basis for

. (Any basis will do.)

. (Any basis will do.)

- Consider the effect on the basis vectors if they were to be in the nullspace of some matrix

meeting the criteria above.

meeting the criteria above.

- Take the corresponding system of linear equations, re-express it as a system involving the entries of

as unknowns and the entries of the basis vectors as coefficients, and show that we can solve the system to find the unknowns.

as unknowns and the entries of the basis vectors as coefficients, and show that we can solve the system to find the unknowns.

- Show that all other vectors in

are also in the nullspace of

are also in the nullspace of  .

.

- Show that any vector in the nullspace of

must also be in

must also be in  .

.

We now proceed to the individual cases:

has dimension

has dimension  . We then have

. We then have  . (If

. (If  has dimension 4 then its basis has four linearly independent vectors. If

has dimension 4 then its basis has four linearly independent vectors. If  then there must be some vector

then there must be some vector  in

in  but not in

but not in  , and that vector must be linearly independent of the vectors in the basis of

, and that vector must be linearly independent of the vectors in the basis of  . But it is impossible to have five linearly independent vectors in a 4-dimensional vector space, so we conclude that

. But it is impossible to have five linearly independent vectors in a 4-dimensional vector space, so we conclude that  .)

.)

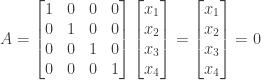

We then must have  for any vector

for any vector  in

in  . This is true when

. This is true when  is equal to the zero matrix. As noted above

is equal to the zero matrix. As noted above  must have exactly four columns and at least

must have exactly four columns and at least  rows. So one possible value for

rows. So one possible value for  is

is

(The matrix  could have additional rows as well, as long as they are all zeros.)

could have additional rows as well, as long as they are all zeros.)

We have thus found a matrix  such that any vector

such that any vector  in

in  is also in

is also in  . Going the other way, any vector

. Going the other way, any vector  in

in  must have four entries (in order for

must have four entries (in order for  to be able to multiply it) so that any such vector

to be able to multiply it) so that any such vector  is also in

is also in  .

.

So if  is a 4-dimensional subspace (namely

is a 4-dimensional subspace (namely  ) then a matrix

) then a matrix  exists such that

exists such that  is the nullspace of

is the nullspace of  .

.

has dimension

has dimension  . The only 0-dimensional subspace of

. The only 0-dimensional subspace of  is that consisting only of the zero vector

is that consisting only of the zero vector  . (If

. (If  contained only a single nonzero vector then it would not be closed under multiplication, since multiplying that vector times the scalar 0 would produce a vector not in

contained only a single nonzero vector then it would not be closed under multiplication, since multiplying that vector times the scalar 0 would produce a vector not in  . If

. If  were not closed under multiplication then it would not be a subspace.)

were not closed under multiplication then it would not be a subspace.)

In this case the matrix  would have to have rank

would have to have rank  . If

. If  then all four columns of

then all four columns of  would have to be linearly independent and

would have to be linearly independent and  would have to have at least four linearly independent rows. Suppose we choose the four elementary vectors

would have to have at least four linearly independent rows. Suppose we choose the four elementary vectors  through

through  as the columns, so that

as the columns, so that

If  we then have

we then have

so that the only solution is  . We have thus again found a matrix

. We have thus again found a matrix  for which

for which  .

.

(Note that any other matrix of rank  would have worked as well: The product

would have worked as well: The product  is a linear combination of the columns of

is a linear combination of the columns of  , with the coefficients being

, with the coefficients being  through

through  . If the columns of

. If the columns of  are linearly independent then that linear combination can be zero only if all the coefficients

are linearly independent then that linear combination can be zero only if all the coefficients  through

through  are zero.)

are zero.)

Having disposed of the easy cases, we now proceed to the harder ones.

has dimension

has dimension  . In this case we are looking for a matrix

. In this case we are looking for a matrix  with rank

with rank  such that

such that  . The matrix

. The matrix  thus must have only one linearly independent column and (more important for our purposes) only one linearly independent row. We need only find a matrix that is 1 by 4. (If desired we can construct suitable matrices that are 2 by 4, 3 by 4, etc., by adding additional rows that are multiples of the first row.)

thus must have only one linearly independent column and (more important for our purposes) only one linearly independent row. We need only find a matrix that is 1 by 4. (If desired we can construct suitable matrices that are 2 by 4, 3 by 4, etc., by adding additional rows that are multiples of the first row.)

Since the dimension of  is 3, any three linearly independent vectors in

is 3, any three linearly independent vectors in  form a basis for

form a basis for  ; we pick an arbitrary set of such vectors

; we pick an arbitrary set of such vectors  ,

,  , and

, and  . For

. For  to be equal to

to be equal to  we must have

we must have  ,

,  , and

, and  . We are looking for a matrix

. We are looking for a matrix  that is 1 by 4, so these equations correspond to the following:

that is 1 by 4, so these equations correspond to the following:

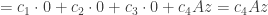

These can in turn be rewritten as the following system of equations:

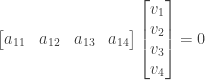

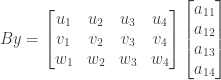

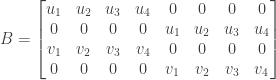

This is a system of three equations in four unknowns, equivalent to the matrix equation  where

where

Since the vectors  ,

,  , and

, and  are linearly independent (because they form a basis for the 3-dimensional subspace

are linearly independent (because they form a basis for the 3-dimensional subspace  ) and the vectors in question form the rows of the matrix

) and the vectors in question form the rows of the matrix  , the rank of

, the rank of  is

is  . We also have

. We also have  , the number of rows of

, the number of rows of  . Since this is true, per 20Q on page 96 there exists at least one solution

. Since this is true, per 20Q on page 96 there exists at least one solution  to the above system

to the above system  . But

. But  is simply the first and only row in the matrix we were looking for, so this in turn means that we have found a matrix

is simply the first and only row in the matrix we were looking for, so this in turn means that we have found a matrix  for which

for which  ,

,  , and

, and  are in the nullspace of

are in the nullspace of  .

.

If  is a vector in

is a vector in  then

then  can be expressed as a linear combination of the basis vectors

can be expressed as a linear combination of the basis vectors  ,

,  , and

, and  for some set of coefficients

for some set of coefficients  ,

,  , and

, and  . We then have

. We then have

So any vector  in

in  is also an element in the nullspace of

is also an element in the nullspace of  .

.

Suppose that  is a vector in the nullspace of

is a vector in the nullspace of  and

and  is not in

is not in  . Since

. Since  is not in

is not in  it cannot be expressed as a linear combination solely of the basis vectors

it cannot be expressed as a linear combination solely of the basis vectors  ,

,  , and

, and  ; rather we must have

; rather we must have

where  is some vector that is linearly independent of

is some vector that is linearly independent of  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

If  is in the nullspace of

is in the nullspace of  then we have

then we have  so

so

If  then either

then either  or

or  . If

. If  then we have

then we have

so that  is actually an element of

is actually an element of  , contrary to our supposition. If

, contrary to our supposition. If  then

then  is an element of the nullspace of

is an element of the nullspace of  . But

. But  has dimension 3 and already contains the three linearly independent vectors

has dimension 3 and already contains the three linearly independent vectors  ,

,  , and

, and  . The fourth vector

. The fourth vector  cannot be both an element of

cannot be both an element of  and also linearly independent of

and also linearly independent of  ,

,  , and

, and  .

.

Our assumption that  is in the nullspace of

is in the nullspace of  but is not in

but is not in  has thus led to a contradiction. We conclude that any element of

has thus led to a contradiction. We conclude that any element of  is also in

is also in  . We previously showed that any element of

. We previously showed that any element of  is also in

is also in  , so we conclude that

, so we conclude that  .

.

For any 3-dimensional subspace  of

of  we can therefore find a matrix

we can therefore find a matrix  such that

such that  is the nullspace of

is the nullspace of  .

.

has dimension

has dimension  . In this case we are looking for a matrix

. In this case we are looking for a matrix  with rank

with rank  such that

such that  . The matrix

. The matrix  thus must have only two linearly independent columns and only two linearly independent rows. We thus look for a matrix that is 2 by 4.

thus must have only two linearly independent columns and only two linearly independent rows. We thus look for a matrix that is 2 by 4.

Since the dimension of  is 2, any two linearly independent vectors in

is 2, any two linearly independent vectors in  form a basis for

form a basis for  ; we pick an arbitrary set of such vectors

; we pick an arbitrary set of such vectors  and

and  . For

. For  to be equal to

to be equal to  we must have

we must have  and

and  . We are looking for a matrix

. We are looking for a matrix  that is 2 by 4, so these equations correspond to the following:

that is 2 by 4, so these equations correspond to the following:

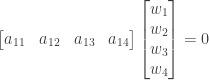

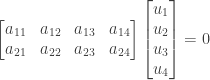

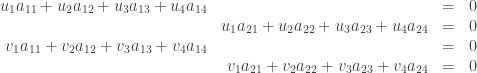

These can in turn be rewritten as the following system of four equations in eight unknowns:

or  where

where

Since the four rows are linearly independent (this follows from the linear independence of  and

and  ) we have

) we have  so that the system is guaranteed to have a solution

so that the system is guaranteed to have a solution  . The entries in

. The entries in  are just the entries of

are just the entries of  so we have found a matrix

so we have found a matrix  for which the basis vectors

for which the basis vectors  and

and  are members of the nullspace.

are members of the nullspace.

Since the basis vectors of  are in

are in  all other elements of

all other elements of  are in

are in  also. By the same argument as in the 3-dimensional case, any vector

also. By the same argument as in the 3-dimensional case, any vector  in

in  must be in

must be in  also; otherwise a contradiction occurs. Thus we conclude that

also; otherwise a contradiction occurs. Thus we conclude that  .

.

For any 2-dimensional subspace  of

of  we can therefore find a matrix

we can therefore find a matrix  such that

such that  is the nullspace of

is the nullspace of  .

.

has dimension

has dimension  . In this case we are looking for a matrix

. In this case we are looking for a matrix  with rank

with rank  such that

such that  . The matrix

. The matrix  thus must have only three linearly independent columns and only three linearly independent rows. We thus look for a matrix that is 3 by 4.

thus must have only three linearly independent columns and only three linearly independent rows. We thus look for a matrix that is 3 by 4.

Since the dimension of  is 1, any nonzero vector

is 1, any nonzero vector  in

in  forms a basis for

forms a basis for  . For

. For  to be equal to

to be equal to  we must have

we must have  . We are looking for a matrix

. We are looking for a matrix  that is 3 by 4, so this equation corresponds to the following:

that is 3 by 4, so this equation corresponds to the following:

This can be rewritten as a system  of three equations with twelve unknowns (

of three equations with twelve unknowns ( ), a system which is guaranteed to have at least one solution due to the linear independence of the three rows of

), a system which is guaranteed to have at least one solution due to the linear independence of the three rows of  . The solution then forms the entries of

. The solution then forms the entries of  , so that we have

, so that we have  . Since

. Since  is a basis for

is a basis for  any other vector in

any other vector in  is also in the nullspace of

is also in the nullspace of  .

.

By the same argument as in the 3-dimensional case, any vector  in

in  must be in

must be in  also; otherwise a contradiction occurs. Thus we conclude that

also; otherwise a contradiction occurs. Thus we conclude that  .

.

For any 1-dimensional subspace  of

of  we can therefore find a matrix

we can therefore find a matrix  such that

such that  is the nullspace of

is the nullspace of  .

.

Any subspace of  must have dimension from 0 through 4. We have thus shown that for any subspace

must have dimension from 0 through 4. We have thus shown that for any subspace  of

of  we can find a matrix

we can find a matrix  such that

such that  . The statement is true.

. The statement is true.

b) Suppose that for some  by

by  matrix

matrix  both

both  and its transpose

and its transpose  have the same nullspace.

have the same nullspace.

The rank  of

of  is also the rank of

is also the rank of  . The rank of

. The rank of  is then

is then  , and the rank of

, and the rank of  is

is  . Since

. Since  we then have

we then have  so that

so that  .

.

The number of rows  of

of  is the same as the number of columns

is the same as the number of columns  of

of  so that

so that  (and thus

(and thus  ) is a square matrix. The statement is true.

) is a square matrix. The statement is true.

c) If  represents the transformation in question, with

represents the transformation in question, with  , we have

, we have

These two quantities are not the same unless  , so for

, so for  the transformation is not linear. The statement is false.

the transformation is not linear. The statement is false.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

and

what is the length of each vector and their inner product?

and

.

and

is then

and

are thus orthogonal.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.