Exercise 2.1.7. Of the following, which are subspaces of  ?

?

(a) the set of all sequences that include infinitely many zeros, e.g.,

(b) the set of all sequences of the form  where

where  from some point onward

from some point onward

(c) the set of all decreasing sequences, i.e.,  for all

for all

(d) the set of all sequences such that  converges to a limit as

converges to a limit as

(e) the set of all arithmetic progressions for which  is constant for all

is constant for all

(f) the set of all geometric progressions of the form  for any choice of

for any choice of  and

and

Answer: (a) This set is not a subspace because it is not closed under addition: If we have  and

and  then both

then both  and

and  are in the set but their sum

are in the set but their sum  is not.

is not.

(b) This set is closed under scalar multiplication: Consider  and suppose for some

and suppose for some  we have

we have  for

for  . We then have

. We then have  . Since we have

. Since we have  for

for  we also have

we also have  for

for  . So

. So  is also a member of the set.

is also a member of the set.

This set is also closed under vector addition. Consider  from above and

from above and  where

where  and for some

and for some  we have

we have  for

for  , and consider the sum

, and consider the sum  . Choose

. Choose  so that

so that  and

and  . Then

. Then  for

for  and

and  for

for  so that

so that  for

for  . The sum

. The sum  is therefore also a member of the set.

is therefore also a member of the set.

Since the set is closed under both vector addition and scalar multiplication and it is a subset of the vector space of infinite sequences, it is a subspace of that vector space.

(c) This set is not a subspace because it is not closed under scalar multiplication: The sequence  is a member of the set, but

is a member of the set, but  is not.

is not.

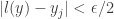

(d) We first check that the set of converging sequences is closed under scalar multiplication. Let  be a member of this set, so that

be a member of this set, so that  exists. Then for any

exists. Then for any  there exists

there exists  such that

such that  for

for  . Now consider

. Now consider  where

where  is any scalar. If

is any scalar. If  then

then  so that it converges to the limit 0.

so that it converges to the limit 0.

Suppose that  and choose any

and choose any  . Since

. Since  exists we can choose

exists we can choose  such that

such that  for

for  . Multiplying both sides by

. Multiplying both sides by  we have

we have  . But

. But  . We therefore see that for any

. We therefore see that for any  we can choose

we can choose  such that

such that  .

.

This means that  exists and is equal to

exists and is equal to  so that for any scalar

so that for any scalar  and converging sequence

and converging sequence  the sequence

the sequence  is also in the set of converging sequences. Since

is also in the set of converging sequences. Since  converges both for

converges both for  and

and  the set is therefore closed under scalar multiplication.

the set is therefore closed under scalar multiplication.

We next check that the set of converging sequences is closed under vector addition. Let  also be a member of this set, so that

also be a member of this set, so that  exists. Then for any

exists. Then for any  there exists

there exists  such that

such that  for

for  .

.

Now consider  and choose any

and choose any  . Since

. Since  exists we can choose

exists we can choose  such that

such that  for

for  , and since

, and since  exists we can choose

exists we can choose  such that

such that  for

for  . Choose

. Choose  such that

such that  and

and  . Adding both sides of the two inequalities we have

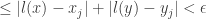

. Adding both sides of the two inequalities we have  for

for  .

.

We have  for any

for any  and

and  , and thus for any

, and thus for any  we have

we have

So for any  we can choose

we can choose  such that

such that  for all

for all  . This means that

. This means that  exists and is equal to

exists and is equal to  so that for any two converging sequences

so that for any two converging sequences  and

and  the sequence

the sequence  is also in the set of converging sequences. The set is therefore closed under vector addition.

is also in the set of converging sequences. The set is therefore closed under vector addition.

Since the set of converging sequences is closed under both vector addition and scalar multiplication and it is a subset of the vector space of infinite sequences, it is a subspace of that vector space.

(e) We first check that the set of arithmetic progressions is closed under scalar multiplication. Let  be a member of this set, so that

be a member of this set, so that  is a constant value

is a constant value  for all

for all  . Then for

. Then for  we have

we have  for all

for all  . The sequence

. The sequence  is therefore also an arithmetic progression, and the set is closed under scalar multiplication.

is therefore also an arithmetic progression, and the set is closed under scalar multiplication.

We next check that the set of arithmetic progressions is closed under vector addition. Let  also be a member of this set, so that

also be a member of this set, so that  is a constant value

is a constant value  for all

for all  . Then for

. Then for  we have

we have

for all  . The sequence

. The sequence  is therefore also an arithmetic progression, and the set is closed under vector addition.

is therefore also an arithmetic progression, and the set is closed under vector addition.

Since the set of arithmetic progressions is closed under both vector addition and scalar multiplication and it is a subset of the vector space of infinite sequences, it is a subspace of that vector space.

(f) The set of geometric progressions is not a subspace because it is not closed under vector addition: For example, suppose that  (for which

(for which  and

and  ), and

), and  (for which

(for which  and

and  ). We then have

). We then have  . For

. For  we have

we have  (from the first element) and

(from the first element) and  (from the second element). If

(from the second element). If  is a geometric progression then the third element should be

is a geometric progression then the third element should be  instead of the actual value of 13. So

instead of the actual value of 13. So  is not a geometrical progression for all geometric progressions

is not a geometrical progression for all geometric progressions  and

and  , and the set is not closed under vector addition.

, and the set is not closed under vector addition.

UPDATE: Fixed typos in the question ( should have been

should have been  ) and in the answers to (b) (

) and in the answers to (b) ( should have been

should have been  ) and (d) (

) and (d) ( should have been

should have been  ).

).

UPDATE 2: Fixed typos in the question and answer for (f) (references to  and

and  should have been to

should have been to  , and a reference to

, and a reference to  should have been to

should have been to  ).

).

UPDATE 3: Fixed the answer for (f); the original answer (claiming that  was not a geometric progression) was incorrect. Thanks go to Samuel for pointing this out.

was not a geometric progression) was incorrect. Thanks go to Samuel for pointing this out.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

form a point, line, or plane? Is it a subspace? Is it the nullspace of

? The column space of

?

corresponds to

and we can substitute into the first equation to obtain

or

. We therefore have

so that the set of solutions

can be represented as

is a free variable. The set of solutions

is therefore a line passing through the origin and the point

.

is the set of all vectors for which

it is by definition the nullspace

of

(see page 68).

is the set of all vectors

that are linear combinations of the columns of

:

are 3 by 1 vectors; the set of solutions

is not the same as the column space of

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.