Review exercise 1.27. State whether the following are true or false. If true explain why, and if false provide a counterexample.

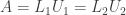

(1) If a matrix  can be factored as

can be factored as  where

where  and

and  are lower triangular with unit diagonals and

are lower triangular with unit diagonals and  and

and  are upper triangular, then

are upper triangular, then  and

and  . (In other words, the factorization

. (In other words, the factorization  is unique.)

is unique.)

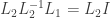

(2) If for a matrix  we have

we have  then

then  is invertible and

is invertible and  .

.

(3) If all the diagonal entries of a matrix  are zero then

are zero then  is singular.

is singular.

Answer: (1) True. Since  and

and  are lower triangular with unit diagonal both matrices are invertible, and their inverses are also lower triangular with unit diagonal. (See the proof of this below at the end of the post.) Similarly since

are lower triangular with unit diagonal both matrices are invertible, and their inverses are also lower triangular with unit diagonal. (See the proof of this below at the end of the post.) Similarly since  and

and  are upper triangular with nonzero diagonal those matrices are invertible as well, and their inverses are also upper triangular with nonzero diagonal.

are upper triangular with nonzero diagonal those matrices are invertible as well, and their inverses are also upper triangular with nonzero diagonal.

We then start with the equation  and multiply both sides by

and multiply both sides by  on the left and by

on the left and by  on the right:

on the right:

This equation reduces to  where

where  is the product matrix. Now since

is the product matrix. Now since  is the product of two lower triangular matrices with unit diagonal (i.e.,

is the product of two lower triangular matrices with unit diagonal (i.e.,  and

and  ), it itself is a lower triangular matrix with unit diagonal. Since

), it itself is a lower triangular matrix with unit diagonal. Since  is the product of two upper triangular matrices (i.e.,

is the product of two upper triangular matrices (i.e.,  and

and  ), it is also an upper triangular matrix. Since

), it is also an upper triangular matrix. Since  is both lower triangular and upper triangular it must be a diagonal matrix, and since its diagonal entries are all 1 we must have

is both lower triangular and upper triangular it must be a diagonal matrix, and since its diagonal entries are all 1 we must have  .

.

Since  we can multiply both sides on the left by

we can multiply both sides on the left by  to obtain

to obtain  or

or  . Similarly since

. Similarly since  we can multiply both sides on the right by

we can multiply both sides on the right by  to obtain

to obtain  or

or  . So the factorization

. So the factorization  is unique.

is unique.

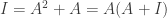

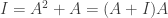

(2) True. Assume  . We have

. We have  so that

so that  is a right inverse for

is a right inverse for  . We also have

. We also have  so that

so that  is a left inverse for

is a left inverse for  . Since

. Since  is both a left and right inverse of

is both a left and right inverse of  we know that

we know that  is invertible and that

is invertible and that  .

.

(3) False. The matrix

has zeros on the diagonal but is nonsingular. In fact we have

Proof of the result used in (1) above: Assume  is a lower triangular matrix with unit diagonal. That

is a lower triangular matrix with unit diagonal. That  is invertible can be seen from Gauss-Jordan elimination (here shown in a 4 by 4 example, although the argument generalizes to all

is invertible can be seen from Gauss-Jordan elimination (here shown in a 4 by 4 example, although the argument generalizes to all  ):

):

Note that in forward elimination each of the diagonal entries of  will remain as is, since each of these entries has only zeros above it; each of the zero entries above the diagonal will remain unchanged as well, for the same reason. When forward elimination completes the left hand matrix will be the identity matrix since it will have zeros below the diagonal (from forward elimination), ones on the diagonal (as noted above), and zeroes above the diagonal (also as noted above). Gauss-Jordan elimination is thus guaranteed to complete successfully, so

will remain as is, since each of these entries has only zeros above it; each of the zero entries above the diagonal will remain unchanged as well, for the same reason. When forward elimination completes the left hand matrix will be the identity matrix since it will have zeros below the diagonal (from forward elimination), ones on the diagonal (as noted above), and zeroes above the diagonal (also as noted above). Gauss-Jordan elimination is thus guaranteed to complete successfully, so  is invertible.

is invertible.

The right-hand matrix at the end of Gauss-Jordan elimination will be the inverse of  . That matrix was produced from the identity matrix by forward elimination only, since backward elimination was not necessary. For the same reason noted above for the left-hand matrix, forward elimination will preserve the unit diagonal in the right-hand matrix and the zeros above it, with the only possible non-zero entries occurring below the unit diagonal. We thus see that if

. That matrix was produced from the identity matrix by forward elimination only, since backward elimination was not necessary. For the same reason noted above for the left-hand matrix, forward elimination will preserve the unit diagonal in the right-hand matrix and the zeros above it, with the only possible non-zero entries occurring below the unit diagonal. We thus see that if  is a lower-triangular matrix with unit diagonal then it is invertible and its inverse

is a lower-triangular matrix with unit diagonal then it is invertible and its inverse  is also a lower-triangular matrix with unit diagonal.

is also a lower-triangular matrix with unit diagonal.

Assume  is an upper triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal. That

is an upper triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal. That  is invertible can be seen from Gauss-Jordan elimination (again shown in a 4 by 4 example):

is invertible can be seen from Gauss-Jordan elimination (again shown in a 4 by 4 example):

Note that forward elimination is not necessary: There are nonzero entries on the diagonal and zeros below them, so we have pivots in every column; therefore the left-hand matrix  is nonsingular and is guaranteed to have an inverse.

is nonsingular and is guaranteed to have an inverse.

We can find that inverse by doing backward elimination to eliminate the entries above the diagonal in the left-hand matrix, and then dividing by the pivots. Note that since backward elimination starts with all zero entries below the diagonal in the right-hand matrix, it will not produce any nonzero entries below the diagonal in that matrix. Also, the diagonal entries in the right-hand matrix are not affected by backward elimination, for the same reason. After backward elimination completes the diagonal entries in the right-hand matrix will still be ones, and any nonzero entries produced will be above the diagonal. Dividing by the pivots in the left-hand matrix will then produce nonzero entries in the diagonal of the right-hand matrix.

The final right-hand matrix after completion of Gauss-Jordan elimination will therefore be an upper triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal entries. We thus see that if  is an upper-triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal then it is invertible and its inverse

is an upper-triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal then it is invertible and its inverse  is also an upper-triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal.

is also an upper-triangular matrix with nonzero diagonal.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

, and try to prove it by induction. Assume that for some

we have

we have

we have

and

, and we might guess that it holds true for

as well. We can test this as follows:

and subtracting it from the second row:

and subtract it from the third row:

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.