Review exercise 1.12. State whether the following are true or false. If a statement is true explain why it is true. If a statement is false provide a counter-example.

(a) If  is invertible and

is invertible and  has the same rows as

has the same rows as  but in reverse order, then

but in reverse order, then  is invertible as well.

is invertible as well.

(b) If  and

and  are both symmetric matrices then their product

are both symmetric matrices then their product  is also a symmetric matrix.

is also a symmetric matrix.

(c) If  and

and  are both invertible then their product

are both invertible then their product  is also invertible.

is also invertible.

(d) If  is a nonsingular matrix then it can be factored into the product

is a nonsingular matrix then it can be factored into the product  of a lower triangular and upper triangular matrix.

of a lower triangular and upper triangular matrix.

Answer: (a) True. If  has the same rows as

has the same rows as  but in reverse order then we have

but in reverse order then we have  where

where  is the permutation matrix that reverses the order of rows. For example, for the 3 by 3 case we have

is the permutation matrix that reverses the order of rows. For example, for the 3 by 3 case we have

If we apply  twice then it restores the order of the rows back to the original order; in other words

twice then it restores the order of the rows back to the original order; in other words  so that

so that  .

.

If  is invertible then

is invertible then  exists. Consider the product

exists. Consider the product  . We have

. We have

so that  is a right inverse for

is a right inverse for  . We also have

. We also have

so that  is a left inverse for

is a left inverse for  as well. Since

as well. Since  is both a left and right inverse for

is both a left and right inverse for  we have

we have  so that

so that  is invertible if

is invertible if  is.

is.

Incidentally, note that while multiplying by  on the left reverses the order of the rows, multiplying by

on the left reverses the order of the rows, multiplying by  on the right reverse the order of the columns. For example, in the 3 by 3 case we have

on the right reverse the order of the columns. For example, in the 3 by 3 case we have

Thus if  exists and

exists and  then

then  exists and consists of

exists and consists of  with its columns reversed.

with its columns reversed.

(b) False. The product of two symmetric matrices is not necessarily itself a symmetric matrix, as shown by the following counterexample:

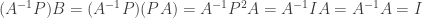

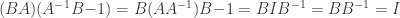

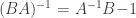

(c) True. Suppose that both  and

and  are invertible; then both

are invertible; then both  and

and  exist. Consider the product matrices

exist. Consider the product matrices  and

and  . We have

. We have

and also

So  is both a left and right inverse for

is both a left and right inverse for  and thus

and thus  . If both

. If both  and

and  are invertible then their product

are invertible then their product  is also.

is also.

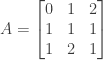

(d) False. A matrix  cannot necessarily be factored into the form

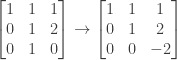

cannot necessarily be factored into the form  because you may need to do row exchanges in order for elimination to succeed. Consider the following counterexample:

because you may need to do row exchanges in order for elimination to succeed. Consider the following counterexample:

This matrix requires exchanging the first and second rows before elimination can commence. We can do this by multiplying by an appropriate permutation matrix:

We then multiply the (new) first row by 1 and subtract it from the third row (i.e., the multiplier  ):

):

and then multiply the second row by 1 and subtract it from the third ( ):

):

We then have

and

So a matrix  cannot always be factored into the form

cannot always be factored into the form  .

.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

into the form

(if

).

exists and has the same form as

.

times the second row from the third row (

) and subtracting

times the second row from the fourth row (

) :

times the second row and subtracting it from the first:

:

having the same form as

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.