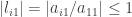

Exercise 1.7.10. When partial pivoting is used show that  for all multipliers

for all multipliers  in

in  . In addition, show that if

. In addition, show that if  for all

for all  and

and  then after producing zeros in the first column we have

then after producing zeros in the first column we have  , and in general we have

, and in general we have  after producing zeros in column

after producing zeros in column  . Finally, show an 3 by 3 matrix with

. Finally, show an 3 by 3 matrix with  and

and  for which the last pivot is 4.

for which the last pivot is 4.

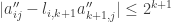

Answer: (a) With partial pivoting we choose the pivot  for each row and column in turn so that the pivot is the largest (in absolute value) of all the candidate pivots in the same column. Thus

for each row and column in turn so that the pivot is the largest (in absolute value) of all the candidate pivots in the same column. Thus  where

where  are all the other candidate pivots. The multipliers

are all the other candidate pivots. The multipliers  are then equal to the candidate pivots divided by the chosen pivot, so that

are then equal to the candidate pivots divided by the chosen pivot, so that  . But since

. But since  we have

we have  .

.

(b) Assume that  for all

for all  and

and  . Without loss of generality assume that

. Without loss of generality assume that  for all

for all  . (If this were not true then we could simply employ partial pivoting and do a row exchange to ensure that this would be the case.) Also assume that

. (If this were not true then we could simply employ partial pivoting and do a row exchange to ensure that this would be the case.) Also assume that  (i.e., the matrix is not singular). We then have

(i.e., the matrix is not singular). We then have  for

for  and thus

and thus  for

for  .

.

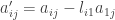

Let  be the matrix produced after the first stage of elimination. Then for

be the matrix produced after the first stage of elimination. Then for  we have

we have  and thus

and thus  and thus

and thus  . For

. For  we have

we have  so that

so that  for

for  . But we have

. But we have  for all

for all  (and thus

(and thus  ) and

) and  for

for  . Thus for the product

. Thus for the product  we have

we have  for

for  and for the difference

and for the difference  we have

we have  for

for  (with the maximum difference occurring when

(with the maximum difference occurring when  and

and  or vice versa).

or vice versa).

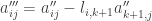

So we have  for

for  and we also have

and we also have  for

for  . For the matrix

. For the matrix  after the first stage of elimination we therefore have

after the first stage of elimination we therefore have  for all

for all  and

and  .

.

Assume that after stage  of elimination we have produced the matrix

of elimination we have produced the matrix  with

with  for all

for all  and

and  and consider stage

and consider stage  of elimination. In this stage our goal is to find an appropriate pivot for column

of elimination. In this stage our goal is to find an appropriate pivot for column  and produce zeros in column

and produce zeros in column  for all rows below

for all rows below  . Without loss of generality assume that

. Without loss of generality assume that  for all

for all  (otherwise we can do a row exchange as noted above). Also assume that

(otherwise we can do a row exchange as noted above). Also assume that  (i.e., the matrix is not singular). We then have

(i.e., the matrix is not singular). We then have  for

for  and thus

and thus  for

for  .

.

Let  be the matrix produced after stage

be the matrix produced after stage  of elimination. Then for

of elimination. Then for  we have

we have  and thus

and thus  and thus

and thus  . For

. For  we have

we have  so that

so that  for

for  . But we have

. But we have  for all

for all  (and thus

(and thus  ) and

) and  for

for  . Thus for the product

. Thus for the product  we have

we have  for

for  and for the difference

and for the difference  we have

we have  for

for  (with the maximum difference occurring when

(with the maximum difference occurring when  and

and  or vice versa).

or vice versa).

So we have  for

for  and we also have

and we also have  for

for  . For the matrix

. For the matrix  after stage

after stage  of elimination (which produces zeros in column

of elimination (which produces zeros in column  ) we therefore have

) we therefore have  for all

for all  and

and  . For

. For  we also have

we also have  for all

for all  and

and  after the first stage of elimination (which produces zeros in column 1). Therefore by induction if in the original matrix

after the first stage of elimination (which produces zeros in column 1). Therefore by induction if in the original matrix  we have

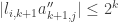

we have  then for all

then for all  if we do elimination with partial pivoting then after stage

if we do elimination with partial pivoting then after stage  of elimination (which produces zeros in column

of elimination (which produces zeros in column  ) we will have a matrix

) we will have a matrix  for which

for which  .

.

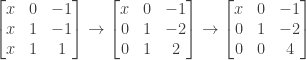

(c) One way to construct the requested matrix is to start with the desired end result and work backward to find a matrix for which elimination will produce that result, assuming that the absolute value of the multiplier at each step is 1 (the largest absolute value allowed under our assumption) and that after stage  we have no value larger in absolute value than

we have no value larger in absolute value than  .

.

Thus in the final matrix (after stage 2 of elimination) we assume we have a pivot of 4 in column 3 but as yet unknown values for the other entries. The successive matrices at the various stages of elimination (the original matrix and the matrices after stage 1 and stage 2) would then be as follows:

We assume a multiplier of  for the single elimination step in stage 2, and prior to that step (i.e., after stage 1 of elimination) we can have no entry larger in absolute value than 2. The successive matrices at the various stages of elimination would then be as follows:

for the single elimination step in stage 2, and prior to that step (i.e., after stage 1 of elimination) we can have no entry larger in absolute value than 2. The successive matrices at the various stages of elimination would then be as follows:

so that subtracting row 2 from row 3 in stage 2 (i.e., using the multiplier  ) would produce the value 4 in the pivot position.

) would produce the value 4 in the pivot position.

We now need to figure out how to produce a value of 2 in the  position and a value of -2 in the

position and a value of -2 in the  position after stage 1 of elimination. Stage 1 consists of two elimination steps, and we assume a multiplier of 1 or -1 for each step; also, all entries in the original matrix can have an absolute value no greater than 1. The original matrix prior to stage 1 of elimination can then be as follows:

position after stage 1 of elimination. Stage 1 consists of two elimination steps, and we assume a multiplier of 1 or -1 for each step; also, all entries in the original matrix can have an absolute value no greater than 1. The original matrix prior to stage 1 of elimination can then be as follows:

with the multiplier  and the multiplier

and the multiplier  (i.e., in stage 1 of elimination we are adding row 1 to row 2 and subtracting row 1 from row 3).

(i.e., in stage 1 of elimination we are adding row 1 to row 2 and subtracting row 1 from row 3).

Now that we have picked entries for column 3 in the original matrix and suitable multipliers for all elimination steps, we need to pick entries for column 1 and column 2 of the original matrix that are consistent with the chosen multipliers and ensure that elimination will produce nonzero pivots in columns 1 and 2.

We first pick values for the  and

and  entries in the matrix after stage 1 of elimination; since we are using the multiplier

entries in the matrix after stage 1 of elimination; since we are using the multiplier  those entries should be the same in order to produce a zero in the

those entries should be the same in order to produce a zero in the  position after stage 2. We’ll try picking a value of 1 for both entries:

position after stage 2. We’ll try picking a value of 1 for both entries:

From above we know that in stage 1 of elimination row 1 is added to row 2 (i.e., the multiplier  ) and row 1 is subtracted from row 3 (i.e., the multiplier

) and row 1 is subtracted from row 3 (i.e., the multiplier  ). Since we have to end up with the same value in the

). Since we have to end up with the same value in the  and

and  positions in either case, the easiest approach is to assume that the

positions in either case, the easiest approach is to assume that the  position in the original matrix has a zero entry, so that adding or subtracting it doesn’t change the preexisting entries for rows 2 and 3:

position in the original matrix has a zero entry, so that adding or subtracting it doesn’t change the preexisting entries for rows 2 and 3:

Finally, we need entries in the first column such that adding row 1 to row 2 and subtracting row 1 from row 3 will produce zero:

This completes our task. We now have a matrix

for which  and

and  , and for which elimination produces a final pivot of 4.

, and for which elimination produces a final pivot of 4.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

how are the rows of

related to the rows of

?

, the product

is a 3 by 3 matrix in which:

.

multiplied by 2.

and the third row of

.

, the product matrix

is a 2 by 3 matrix in which:

.

is a permutation matrix that reverses the order of rows, so that in the product

:

.

.

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.