In the previous post I discussed multiplying block diagonal matrices as part of my series on defining block diagonal matrices and partitioning arbitrary square matrices uniquely and maximally into block diagonal form (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, and part 5). In this final post in the series I discuss the inverse of a block diagonal matrix. In particular I want to prove the following claim:

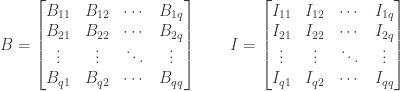

If  is a block diagonal matrix with

is a block diagonal matrix with  submatrices on the diagonal then

submatrices on the diagonal then  is invertible if and only if

is invertible if and only if  is invertible for

is invertible for  . In this case

. In this case  is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to

is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to  , with

, with  so that

so that

Proof: This is an if and only if

statement, so I have to prove two separate things:

- If

is invertible then

is invertible then  is a block diagonal matrix that has the form described above.

is a block diagonal matrix that has the form described above.

- If there is a block diagonal matrix as described above then it is the inverse

of

of  .

.

a) Let  be an

be an  by

by  square matrix partitioned into block diagonal form with

square matrix partitioned into block diagonal form with  row and column partitions:

row and column partitions:

and assume that  is invertible. Then a unique

is invertible. Then a unique  by

by  square matrix

square matrix  exists such that

exists such that  .

.

We partition both  and

and  into block matrices in a manner identical to that of

into block matrices in a manner identical to that of  . In our framework

. In our framework identically partitioned

means that the  partitions of

partitions of  can be described by a partition vector

can be described by a partition vector  of length

of length  , with

, with  containing

containing  rows and columns. We can then take that partition vector

rows and columns. We can then take that partition vector  and use it to partition

and use it to partition  and

and  in an identical manner. (This works because

in an identical manner. (This works because  and

and  are also

are also  by

by  square matrices.)

square matrices.)

We then have

Since  , from the previous post on multiplying block matrices we have

, from the previous post on multiplying block matrices we have

We can rewrite the above sum as follows:

For both sums we have  for all terms in the sums, and since

for all terms in the sums, and since  is in block diagonal form we have

is in block diagonal form we have  for all terms in the sums, so that

for all terms in the sums, so that

But  is the identity matrix, with 1 on the diagonal and zero for all other entries. If

is the identity matrix, with 1 on the diagonal and zero for all other entries. If  then the submatrix

then the submatrix  will contain all off-diagonal entries, so that

will contain all off-diagonal entries, so that  , and therefore

, and therefore  for

for  . But

. But  is an arbitrary matrix and thus

is an arbitrary matrix and thus  may be nonzero. For the product of

may be nonzero. For the product of  and

and  to always be zero when

to always be zero when  , we must have

, we must have  when

when  . Thus

. Thus  is in block diagonal form when partitioned identically to

is in block diagonal form when partitioned identically to  .

.

When  we have

we have  . But

. But  has 1 for all diagonal entries and 0 for all off-diagonal entries; it is simply a version of the identity matrix with

has 1 for all diagonal entries and 0 for all off-diagonal entries; it is simply a version of the identity matrix with  rows and columns. Since the product

rows and columns. Since the product  is equal to the identity matrix,

is equal to the identity matrix,  is a right inverse of

is a right inverse of  .

.

We also have  , so that

, so that

We can rewrite the above sum as follows:

For both sums we have  for all terms in the sums, and since

for all terms in the sums, and since  is in block diagonal form we have

is in block diagonal form we have  for all terms in the sums, so that

for all terms in the sums, so that  . For

. For  both sides of the equation are zero (since both

both sides of the equation are zero (since both  and

and  are in block diagonal form), and for

are in block diagonal form), and for  we have

we have  . But

. But  is the identity matrix, and thus

is the identity matrix, and thus  is a left inverse of

is a left inverse of  for

for  .

.

Since  is both a right and left inverse of

is both a right and left inverse of  for

for  , we conclude that

, we conclude that  is invertible for

is invertible for  and has inverse

and has inverse  . We also know that

. We also know that  is partitioned into block diagonal form, so we conclude that

is partitioned into block diagonal form, so we conclude that

b) Let  be an

be an  by

by  square matrix partitioned into block diagonal form with

square matrix partitioned into block diagonal form with  row and column partitions:

row and column partitions:

and assume that  is invertible for

is invertible for  . Then for

. Then for  a unique

a unique  by

by  square matrix

square matrix  exists such that

exists such that  .

.

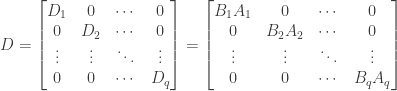

We now construct block diagonal matrix  with the matrices

with the matrices  as its diagonal submatrices:

as its diagonal submatrices:

Since each  is a square matrix with the same number of rows and columns as the corresponding submatrix

is a square matrix with the same number of rows and columns as the corresponding submatrix  of

of  , the matrix

, the matrix  will also be a square matrix of size

will also be a square matrix of size  by

by  , and as a block diagonal matrix

, and as a block diagonal matrix  is partitioned identically to

is partitioned identically to  .

.

Now form the product matrix  , which is also an

, which is also an  by

by  matrix. Since

matrix. Since  and

and  are identically partitioned block diagonal matrices, per the previous post on multiplying block diagonal matrices we know that

are identically partitioned block diagonal matrices, per the previous post on multiplying block diagonal matrices we know that  is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to

is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to  and

and  , with each

, with each  :

:

But we have  ,

,  , and therefore

, and therefore  ,

,  . Since every submatrix

. Since every submatrix  has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, the matrix

has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, the matrix  itself has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, so that

itself has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, so that  . The matrix

. The matrix  is therefore a

is therefore a left right inverse for  .

.

Next form the product matrix  , which is also an

, which is also an  by

by  block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to

block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to  and

and  , with each

, with each  :

:

But we have  ,

,  , and therefore

, and therefore  ,

,  . Since every submatrix

. Since every submatrix  has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, the matrix

has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, the matrix  itself has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, so that

itself has 1 on the diagonal and zero otherwise, so that  . The matrix

. The matrix  is therefore a

is therefore a right left inverse for  .

.

Since  is both a left and a right inverse for

is both a left and a right inverse for  ,

,  is therefore the inverse

is therefore the inverse  of

of  . From the way

. From the way  was constructed we then have

was constructed we then have

Combining the results of (a) and (b) above, we conclude that if  is a block diagonal matrix with

is a block diagonal matrix with  submatrices on the diagonal then

submatrices on the diagonal then  is invertible if and only if

is invertible if and only if  is invertible for

is invertible for  . In this case

. In this case  is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to

is also a block diagonal matrix, identically partitioned to  , with

, with  .

.

UPDATE: Corrected two instances where I referred to the matrix  as a left inverse of

as a left inverse of  instead of a right inverse, and vice versa.

instead of a right inverse, and vice versa.

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

Buy me a snack to sponsor more posts like this!

.

and start by multiplying the first row by the multiplier

and subtracting it from the second row:

and subtract it from the third row:

and subtract it from the third row:

entries) and

is then

and subtracting it from the second:

entries) and

is then

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.