Exercise 1.6.12. Suppose that A is an invertible matrix and has one of the following properties:

(1) A is a triangular matrix.

(2) A is a symmetric matrix.

(3) A is a tridiagonal matrix.

(4) All the entries of A are whole numbers.

(5) All the entries of A are rational numbers (i.e., fractions or whole numbers).

Which of the above would also be true of the inverse of A? Prove your conclusions or find a counterexample if false.

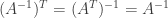

Answer: (1) Assume that A is an invertible triangular matrix. A can be either upper triangular or lower triangular. We first assume that A is upper triangular, such that

We use Gauss-Jordan elimination to find the inverse of A. Since A is upper triangular forward elimination is complete, since all entries beneath the diagonal of A are already zero. (Moreover, the diagonal entries of A are nonzero, since if there were any zeros in the pivot position A would be singular and hence not invertible.)

We can thus proceed immediately to backward elimination. The first backward elimination step multiplies all entries in the last row and subtracts them from the next-to-last row. But we still have I on the righthand side, and I has all zero entries below the diagonal just as A does. We will be multiplying zero entries below the diagonal of the right-hand matrix (i.e., in the last row), and then subtracting the resulting zero values from other zero values below the diagonal of the right-hand side (i.e., in the next to last row). As a result, after the first backward elimination step all the entries below the diagonal of the right-hand matrix will still be zero.

By similar reasoning the second step of backward elimination will also produce zero entries below the diagonal of the right-hand matrix, and so will each subsequent step. When Gauss-Jordan backward elimination finally completes, the final right-hand matrix, which is the inverse of A, will thus have all zero entries below the diagonal and will be upper triangular. Thus if A is upper triangular and invertible then the inverse of A will be upper triangular as well.

Now suppose A is invertible and lower triangular, so that

Again we do Gauss-Jordan elimination to find the inverse of A. The first forward elimination step multiplies all entries in the first row and subtracts them from the second row. We will be multiplying zero entries above the diagonal of both the left-hand and the right-hand matrix (i.e., in the first row), and then subtracting the resulting zero values from other zero values above the diagonal of the left-hand and the right-hand matrix (i.e., in the second row). As a result, after the first forward elimination step all the entries above the diagonal of both the left-hand and the right-hand matrix will still be zero.

By similar reasoning the second step of forward elimination will also produce zero entries above the diagonal of both the left-hand and right-hand matrix, and so will each subsequent step. After forward elimination completes both the lefthand matrix and the righthand matrix will thus have zeroes above the diagonal. Since the lefthand matrix has all zeroes above the diagonals there is no need to do backward elimination, and all that remains is to divide both matrices by the values in the pivot positions.

This division will leave any zero entries still zero, so the final righthand matrix, i.e., the inverse of A, will also have zeroes above the diagonal and will be lower triangular. Thus if A is lower triangular and invertible then the inverse of A will be lower triangular as well. Combining these two results, if A is an invertible triangular matrix then the inverse of A is triangular as well.

(2) Suppose that A is an invertible symmetric matrix. Since A is symmetric we have

and since A is invertible we have

But since the inverse of A is equal to its own transpose it is a symmetric matrix. Thus if A is an invertible symmetric matrix then the inverse of A is also symmetric.

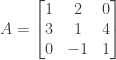

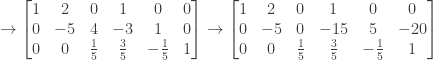

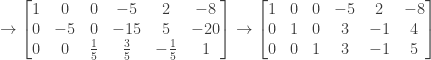

(3) We attempt to find a counter-example by constructing a 4 by 4 tridiagonal matrix A such that:

and then use Gauss-Jordan elimination to find its inverse:

We therefore have

which is not a tridiagonal matrix. Therefore if A is an invertible tridiagonal matrix it is not necessarily the case that the inverse of A is also tridiagonal.

(4) We attempt to find a counter-example by constructing a 2 by 2 matrix A with whole number entries:

We then have

which does not have whole number entries. Therefore if A is an invertible matrix whose entries are all whole numbers, it is not necessarily the case that all the entries of the inverse of A are also whole numbers.

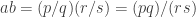

(5) Suppose that A is an invertible matrix and that all of the entries of A are rational numbers (whole numbers or fractions). For each i and j the corresponding entry of A is thus of the form

where p is some integer and q is some non-zero integer. (If q is 1 then the entry is a whole number.)

We use Gauss-Jordan elimination to find the inverse of A, and without loss of generality assume that no row exchanges are required for the first step. The first forward elimination step multiplies all entries in the first row and subtracts the results from each of the remaining rows, with the multipliers for each row being computed as the pivot in the first row divided by each of the entries in the same column of the remaining rows (assuming those entries are nonzero).

But a rational number divided by a nonzero rational number is itself a rational number, as is a rational number multiplied by another rational number, and as is a rational number added to or subtracted from another rational numbers. (See below for the proof of this.) Since all the entries in A are rational numbers, as are all in the entries in I (the right-hand matrix for the first elimination step), all the entries in the left-hand and right-hand matrices resulting from the first forward elimination step are also rational numbers.

By similar reasoning the second forward elimination step will produce only rational numbers, as will any subsequent elimination step. Similarly backward elimination will produce only rational numbers at each step, as will the final division by the nonzero pivots. The right-hand matrix after the final step, i.e., the inverse of A, thus has all entries being rational numbers. So if A is an invertible matrix with all rational entries then the inverse of A will also have all rational entries.

Proof that the product, sum, and difference of two rational numbers are themselves rational numbers, as is the result of dividing a rational number by a nonzero rational number:

Let a and b be rational numbers. We then have

for some p, q, r, and s where p and r are integers and q and s are nonzero integers.

The product of a and b is then

Since p and q are both integers their product is an integer, and since r and s are both nonzero integers their product is also a nonzero integer. The product of a and b can thus be expressed as an integer divided by a nonzero integer, and thus is a rational number.

The sum of a and b is then

The product of p and s is an integer, as is the product of q and r, and thus their sum is an integer as well. Also, since q and s are nonzero integers their product is a nonzero integer as well. The sum of a and b can thus be expressed as an integer divided by a nonzero integer, and thus is a rational number.

The difference of a and b can be show to be a rational number by a similar argument.

Finally, if b is nonzero then a divided by b is

Since p and s are integers their product is an integer as well. We also have q as a nonzero integer and since b is nonzero r is also a nonzero integer, so that the product of q and r is a nonzero integer as well. The result of dividing a by b can thus be expressed as an integer divided by a nonzero integer, and thus is a rational number.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

be an

by

square matrix, and suppose we partition

into submatrices with

row and column partitions:

is a block diagonal matrix (or, alternately, has been partitioned into block diagonal form) if

.

to be in block diagonal form with a single partition, i.e., when

. (This follows from the Wolfram Mathworld definition above, which defines a block diagonal matrix as a special type of diagonal matrix, and also from the Wolfram Mathworld definition of a diagonal matrix, which allows it to have just one element.)

is trivially in block diagonal form if considered to have a single partition, and a diagonal matrix

is also in block diagonal form as well, with each entry on the diagonal considered as a submatrix with a single entry. What about the in-between cases though? Is there a

by

square matrix

we can uniquely and maximally partition

into a block diagonal matrix with

submatrices, for some

where

, such that

cannot also be partitioned as a block diagonal matrix with

partitions, where

.

into block diagonal form as

.

as described.