Exercise 1.4.14. Show example 2×2 matrices having the following properties:

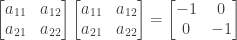

- A matrix A with real entries such that

- A nonzero matrix B such that

- Two matrices C and D with nonzero product such that CD = -DC

- Two matrices E and F with all nonzero entries such that EF = 0

Answer: (a) If  we have

we have

We then have the following:

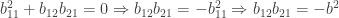

Assume that  . From the first and fourth equations above we then have

. From the first and fourth equations above we then have

which reduces to the single equation  . Assume that

. Assume that  for some real nonzero a. We then have

for some real nonzero a. We then have  .

.

So a matrix A meeting the above criterion is

where a is nonzero, for which

We can obtain a specific example of A by setting a = 1, in which case

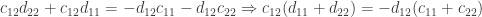

(b) If  we have

we have

We then have the following:

Assume that  and

and  are nonzero, and choose

are nonzero, and choose  where b is a nonzero real number. Then from the second and third equations we have

where b is a nonzero real number. Then from the second and third equations we have  . From the first and fourth equations we should have

. From the first and fourth equations we should have  and this is indeed the case, since

and this is indeed the case, since  .

.

Substituting into the first equation we then have

(We could have used the fourth equation just as well for this.)

If we choose  we then have

we then have  . This gives us the following matrix

. This gives us the following matrix

for which

If we set b = 1 then we obtain the specific example

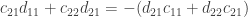

(c) If  we have

we have

By the rules of matrix multiplication we then have

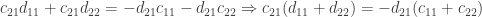

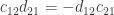

Taking the second and third equations above and rearranging terms we have

The easiest way to satisfy the resulting equations is to set

We then have

which gives us the following equations:

which reduce to the single equation  . If we set

. If we set  where

where  then we have

then we have  . If we set

. If we set  where

where  then

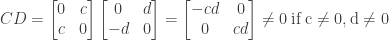

then  . We then have the following matrices C and D:

. We then have the following matrices C and D:

with

and

One example of C and D can be found by setting  :

:

(d) Using the result of (b) above, if we set

then we will have EF = 0 with both E and F having all nonzero entries.

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

for all n.

if n is even and

if n is odd.

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.