Exercise 1.4.11. State whether the following statements are true or false. If a given statement is false, provide a counterexample to the statement.

- For two matrices A and B, if the first column of B is identical to the third column of B then the first column of AB is identical to the third column of AB.

- If the first row of B is identical to the third row of B then the first row of AB is identical to the third row of AB.

- If the first row of A is identical to the third row of A then the first row of AB is identical to the third row of AB.

- The square of AB is equal to the square of A times the square of B.

Answer: Assume that A is an m x n matrix and B is an n x p matrix.

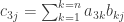

1. Each entry  in the first column of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the ith row of A with the first column of B:

in the first column of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the ith row of A with the first column of B:

Similarly, each entry  in the third column of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the ith row of A with the third column of B:

in the third column of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the ith row of A with the third column of B:

If the first column of B is equal to the third column of B then we have

for all

for all

We then have

so that the first column of AB is equal to the third column of AB. The statement is therefore true.

2. Each entry  in the first row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the first row of A with the jth column of B:

in the first row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the first row of A with the jth column of B:

Similarly, each entry  in the third row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the third row of A with the jth column of B:

in the third row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the third row of A with the jth column of B:

If the first and third rows of A are different then their inner products with each of the columns of B are not guaranteed to be equal in the general case, and thus the first and third rows of AB are not guaranteed to be equal in the general case. The statement is therefore false.

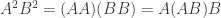

By making the first and third rows of B equal (as stated), but the first and third rows of A different, we can construct a suitable counterexample where the first and third rows of AB are different:

3. As stated in the previous item, each entry  in the first row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the first row of A with the jth column of B:

in the first row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the first row of A with the jth column of B:

and each entry  in the third row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the third row of A with the jth column of B:

in the third row of AB is formed by taking the inner product of the third row of A with the jth column of B:

If the first row of A is equal to the third row of A then their inner products with the jth column of B will be the same, and this implies in turn that each entry in the first row of AB will be equal to the corresponding entry in the third row of AB. The atatement is therefore true.

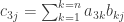

4. We can express the square of AB as follows:

using the definition of the square of AB and the associativity of matrix multiplication.

Similarly we can express the square of A times the square of B as:

Since matrix multiplication is not commutative  in the general case, which implies from the equations above that

in the general case, which implies from the equations above that  in the general case. The statement is therefore false.

in the general case. The statement is therefore false.

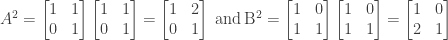

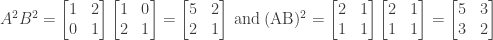

We can find a counterexample by finding two matrices A and B where  . For example, if

. For example, if

we have

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

and

. Then

for i > j, C = AB is an upper triangular matrix as well.

if i < j.)

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fourth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.