Exercise 3.3.13. Using least squares, find the line that is the best fit to the following measurements:

at

at

at

at

at

at

at

at

Also, given the matrix

find the projection of  onto the column space

onto the column space  .

.

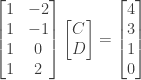

Answer: Assuming that the line in question has the form  the problem can be expressed as that of finding a solution to the system

the problem can be expressed as that of finding a solution to the system

or  where

where  is the exact solution.

is the exact solution.

In this case there is no exact solution, so we look for the least squares solution  that minimizes the error vector

that minimizes the error vector  . The error vector is minimized when it is orthogonal to the column space of

. The error vector is minimized when it is orthogonal to the column space of  and is therefore in the left nullspace of

and is therefore in the left nullspace of  . We then have

. We then have  so that

so that  is a solution to the system

is a solution to the system  .

.

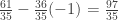

We have

and

so that the system  reduces to

reduces to

or

expressed as a system of equations.

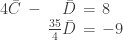

Multiplying the first equation by  and adding it to the second equation produces the system

and adding it to the second equation produces the system

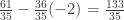

From the second equation we have  . Substituting that value into the first equation we have

. Substituting that value into the first equation we have  or

or  .

.

The line of best fit is therefore  .

.

Given the matrix

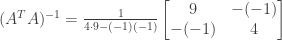

the projection matrix  onto the column space of

onto the column space of  can be computed as

can be computed as

From above we have

so that its inverse is

We then have

The projection of the vector  onto the column space of

onto the column space of  is then

is then

The vector  corresponds to the points on the least squares line of best fit

corresponds to the points on the least squares line of best fit  for the times

for the times  :

:

NOTE: This continues a series of posts containing worked out exercises from the (out of print) book Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Third Edition by Gilbert Strang.

by Gilbert Strang.

If you find these posts useful I encourage you to also check out the more current Linear Algebra and Its Applications, Fourth Edition , Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fifth Edition

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fifth Edition and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books .

.

at

use least squares to find the line of best fit of the form

.

as follows:

. We have

is then

and from the first equation we have

. The line of best fit is therefore

.

by Gilbert Strang.

, Dr Strang’s introductory textbook Introduction to Linear Algebra, Fifth Edition

and the accompanying free online course, and Dr Strang’s other books

.